Jill McClary-Gutierrez

Combining Microbiology and Water Health

“Just because we live in different jurisdictions doesn’t mean the water cares. It will flow where it flows. And if we’re going to have a sustainable and informed approach to solve some of these problems, it requires that holistic view.”

Meet Jill. A native of Chicagoland, she studied environmental engineering at the University of Illinois and became motivated by how human health relates to environmental quality after involvement in her undergraduate chapter of Engineers Without Borders. That spark led Jill to pursue graduate studies in California where she researched waterborne bacteria impacting recreational water quality at beaches. In the course of her doctoral research, she read many papers by Dr. Sandra McLellan from the UW-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences—Sandra is known as a leader in the field, whom Jill credits with “really digging deep into the causes” of recreational water quality impairments. When a postdoctoral research opportunity emerged in Dr. McLellan’s lab, Jill, a newly minted PhD, jumped at the chance. For the past two-plus years at SFS, she’s worked not only with Dr. McLellan but also with Dr. Ryan Newton and Dr. Val Klump on a interdisciplinary project to pinpoint the sources and timing of different contamination pulsing through our waterways after heavy rains. Jill gains from all three scientists’ perspectives—Newton’s expertise on microbial genomics, Klump’s expertise on sediment chemistry, and McLellan’s expertise on tracking novel gut bacterial indicators—to alert the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District and other local regulatory entities with detailed data on how rural and urban areas contribute distinct pollution to our waters when it storms.

The story emerging from the data Jill and team members from three labs have worked intensively to sample over two years during Milwaukee-area storms is a tale of two pulses of pollution—one from urban sources and a second from rural sources. Which makes intuitive sense if you stop to think about it, given how large the Milwaukee River watershed is—stretching north into the farmland of Fond du Lac County. But Jill and the McLellan lab are using DNA analysis to fine-tune our understanding of both the pollution sources we see—and those we don’t see. Both the visible sediment contamination and the invisible bacterial contamination impact Milwaukee’s water quality in different ways and are subject to different regulatory goals that depend upon solid science to address.

The first pulse is urban: contamination from aging sewer lines and surface runoff in the metro area can wash into the river and lake during heavy rains—or from direct sewage discharge during Combined Sewer Overflows if the sewer system itself becomes overwhelmed.

The second pulse is rural: much more sediment is generally washed into the water from land far beyond the city, farther north in the watershed. The flushing of all this sediment still causes issues in the harbor and river bottom. Both must be dredged, the former to maintain navigation and the latter to remove sediment deposited years ago with legacy contaminants toxic for fish and wildlife. Sometimes this rural pulse also contains traces of bacteria found in cow guts—evidence of animal waste washing into the water.

Jill and the McLellan lab test for two different strains of Bacteroides, respectively associated with human and cow waste, and correlate those signals with chemical signatures from sediment analyzed by Dr. Val Klump’s lab. It takes a hard-working team to gather and make sense of all the data. Jill and the team ventured out to different sites on the Milwaukee River, sometimes under heavy downpours, to collect water samples during heavy rain events in 2018 and 2019. They issued a report to the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District, which funded the study, and expect the research will inform regional efforts among multiple municipalities subject to meeting regulatory goals for the amount of sediment and bacterial pollution in their waterways.

“It’s a very interconnected system,” Jill notes. “Just because we live in different jurisdictions doesn’t mean the water cares. It will flow where it flows. And if we’re going to have a sustainable and informed approach to solve some of these problems, it requires that holistic view.”

From the Field to the Lab

A DNA sample tube. The McLellan lab uses distinct bacterial DNA markers like fingerprints to suss out the source of water pollution.

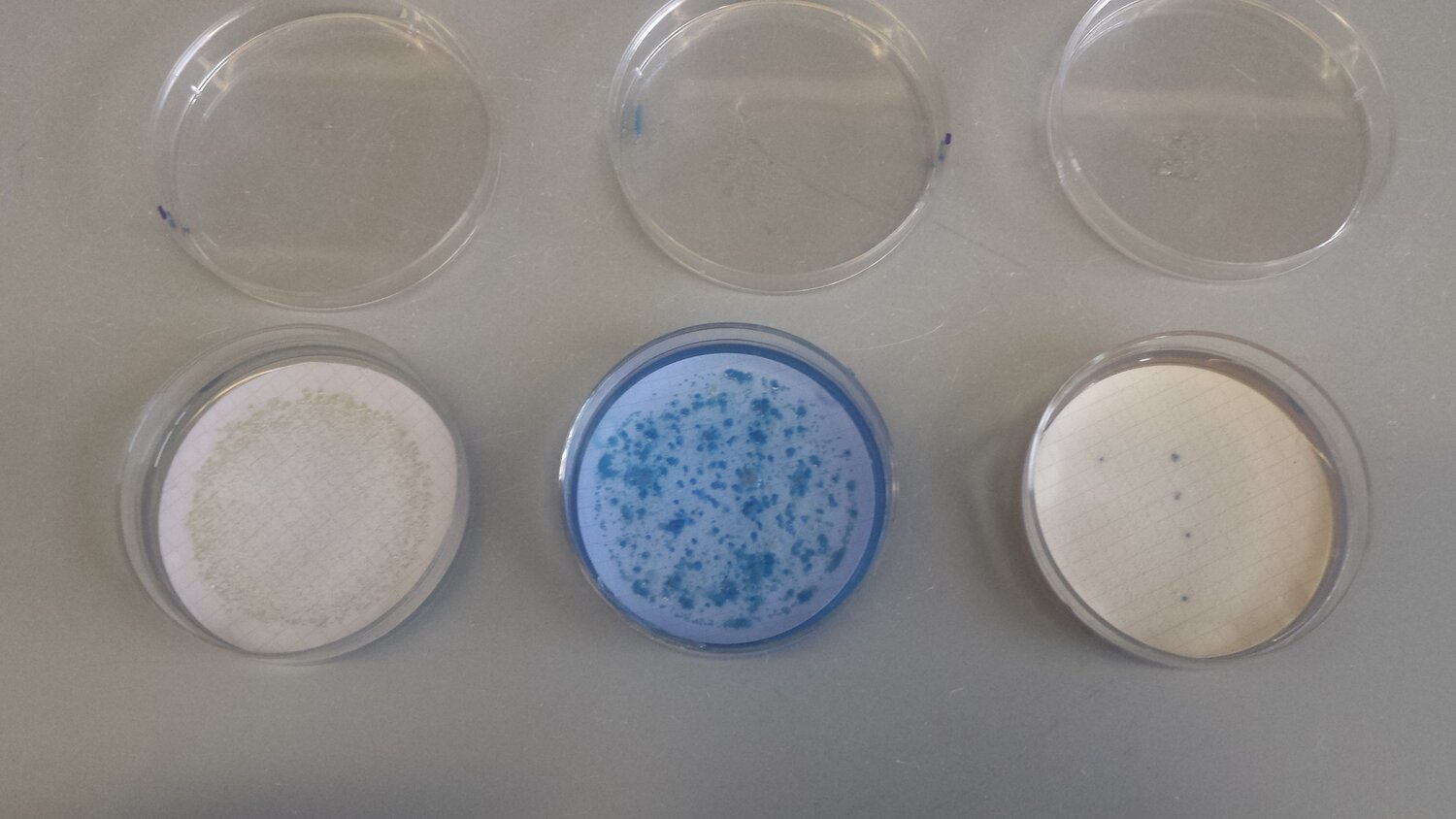

The blue spots in the dishes are fecal bacterial colonies growing from water samples collected in the field.

Sampling site at Jones Island under the Hoan Bridge.

Wilson (undergrad) & Jessie (technician from Dr. Val Klump’s lab) collecting sediment from the Milwaukee River at Saukville, Wis.