Dr. Val Klump

A Freshwater Oceanographer

Inspired to Save Our Lakes

“The Lakes are really just a reflection of what we do on land.”

Meet Val. As a young boy in Michigan, he spent summers on Lake Huron and exploring inland lakes by boat. Inspired by Jacques Cousteau, Val knew he early he wanted to be an oceanographer. Fresh out of grad school at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Val came to Milwaukee some 40 years ago to take an open research position at the UWM Center for Great Lakes Studies. (He jokes that he had never heard of the Milwaukee university but he had heard of the Great Lakes, which he is apt to describe as “inland seas” that hold 20% of Earth’s surface freshwater.) The Center where he held his first postgraduate job researching those Great Lakes has since evolved into the School of Freshwater Sciences, and today Val serves as its dean and a professor. As a biogeochemist—or “a mud scientist” as he jokes—Val, his fellow researchers, and crew of the research vessel Neeskay have years of experience studying Green Bay’s “dead zones” and addressing other big-picture questions about the Great Lakes that are critical to our understanding of how to protect and restore them. Val has already achieved one dream: he feels privileged to be a freshwater oceanographer.

Restoring the Great Lakes to “fishable, swimmable, and drinkable” status motivates the scientific enterprise Val leads at the School of Freshwater Sciences. “For their size [the Great Lakes] are surprisingly fragile ecosystems. We can screw them up. We have screwed them up. But we have the ability to restore them too, and we should get on with that,” he says. “But you cannot restore anything that you don’t understand... Otherwise you wouldn’t know what to do. So that’s job one for us. Our major goal at the school in terms of research is understanding how the ecosystem functions.”

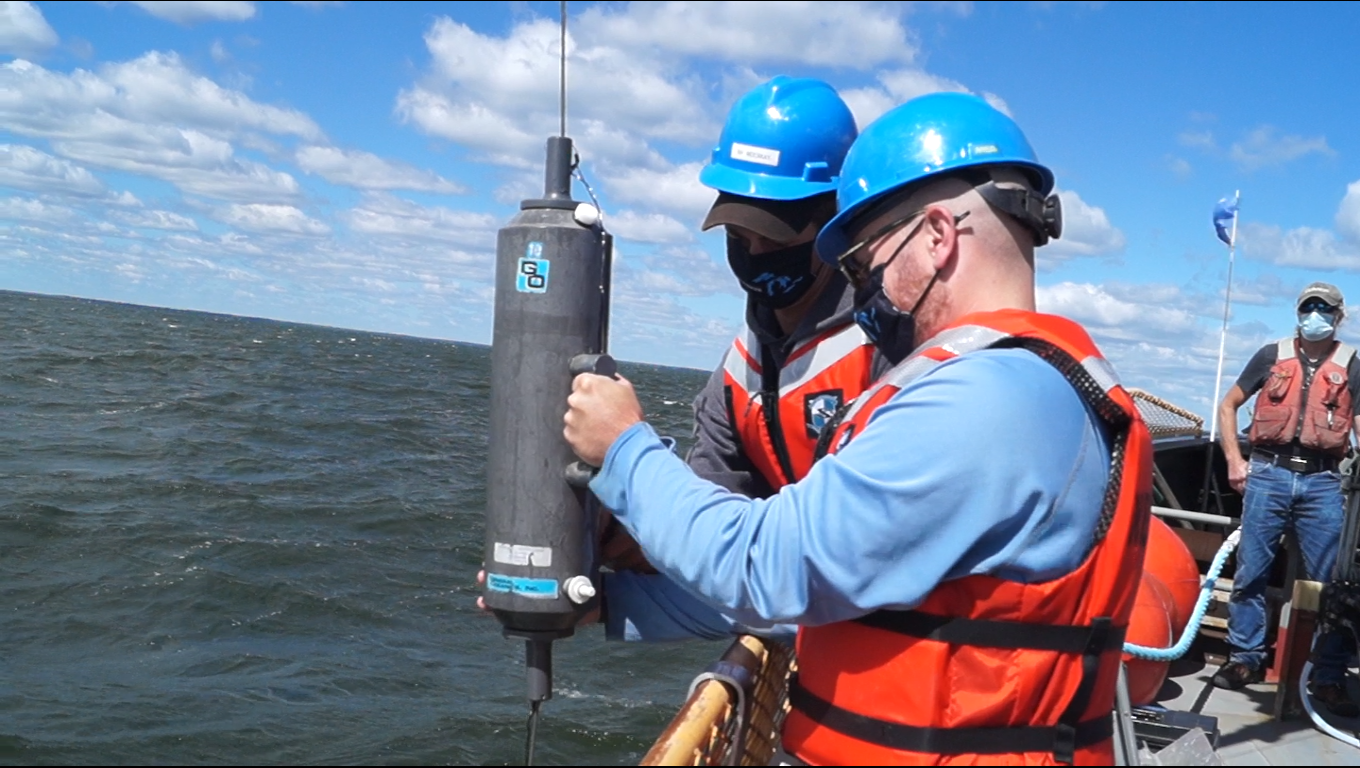

Students retrieve a Niskin bottle from the Neeskay in late summer 2020. The bottle captures a water sample from Green Bay and allows for a particular slice of the water column to be analyzed for oxygen saturation and other factors.

The Health of Green Bay

If Green Bay were the scene of the crime, Val and the crew of the Neeskay plus an ensemble cast of student researchers learning hands-on how to do research—would be gumshoe detectives methodically slogging their way through clues in the mud dredged from the bottom of the bay. The mud tells a story, if you know what questions to ask—and have a trusty research vessel with an experienced crew.

In late summer 2020 the Neeskay motored its way from Milwaukee into Green Bay to conduct a sampling cruise where student researchers plunged instruments into the deep like doctors taking vital measurements of the body’s overall health. Green Bay plays host to just about every ill plaguing the Great Lakes—high nutrient loads running off farm fields, suburban yards, and urban streets make their way into the rivers and streams of the Fox River watershed like too much bad cholesterol saturating the arteries that feed the human heart. Because Green Bay is relatively shallow and sequestered, excessive nutrients that flow into the bay trigger massive blooms of blue-green algae, typically during the late summer when the water is warmest, and then die en masse, sinking to the lake bottom where their decomposition sucks oxygen from the water. Because lake waters are thermally stratified during the summer, with warmer surface water separated from deeper colder water (due to simple physics you can test out in your own bathtub), there’s not enough mixing of oxygen-rich surface waters to replenish that which is withdrawn below.

To switch metaphors to consider elements as financial resources, the lake’s oxygen budget is overdrawn. There’s no way to relieve the deficit until much later in the year when cooler fall temperatures and higher winds churn the waters, mixing fresh dissolved oxygen from the air down to the deep. Low levels of dissolved oxygen during the summer mean that fish and other macroinvertebrates can’t live there—in parts of the bottom Green Bay becomes a “dead zone.” That means the multimillion-dollar sportfishing industry and Wisconsin tourism intimately tied to healthy Great Lakes are in for a world of hurt, not to mention other consequences of an aquatic food web with a big chunk hacked away. If it all sounds dire, add on a warming climate which is increasing the temperature of both air and water, intensifying those harmful algal blooms—not to mention also leading to more intense storms responsible for huge pulses of nutrient-polluted runoff into our waters—plus invasive mussels now carpeting the lakebed that change how nutrients cycle in the lake, and the situation is even worse. The Lake is a patient suffering from multiple chronic illnesses. If it could, Green Bay would be stumbling in to the nearest emergency room.

Which is not to say nothing can be done. Val and the crew of the Neeskay are poring through mud samples dredged from the deep precisely because they know we can do something. But only good science informed by both thorough sampling and comprehensive models can point the way to precisely what actions will make a difference in a rapidly changing system. To obtain samples, you need a boat. Even though the Neeskay is homeported in Milwaukee, it’s one of the only research vessels out on the Lakes. The School of Freshwater Sciences is dedicated to providing resource managers with the best advice about what to do to improve the health of Green Bay. That’s why Val, with his decades of experience and commitment to training the next generation of scientists, is here.

Every mud sample provides a signal of how much oxygen is actually in the deeper layers of the bay. Each slice of mud from a sediment core is one more piece of crucial data. It’s like the difference between seeing your doctor once in a blue moon and you taking daily blood pressure measurements. The more mud samples Val’s team analyzes, the finer our understanding of just how unhealthy Green Bay actually is, and the better our sense of what prescription will make a difference. Combining that data with measurements of how many nutrients are flowing into the bay and plugging it all into a scientific model that lets researchers account for—or at least adjust variations based on climate change—and the end result is a defensible bracket of nutrient loading limits that we can say with a high degree of confidence will or will not help in the fight to make the dead zones come alive again. It may be just a number to some, but if it’s the right number, we can rally farmers, industry, cities, and the public around it in good faith to heal the water.

“The Lakes are really just a reflection of what we do on land,” Val explains. “The problem of Green Bay is that there’s an excessive amount of nutrients and suspended sediments that are washing off the land from the various processes, from agriculture to industry to urban runoff to the guy who runs his fertilizer spreader across the sidewalk when he’s doing his lawn—all of that washes into the Lake. And that stimulates algal blooms. And you get these excessive algal blooms which sink to the bottom, and they decompose, that decomposition process uses up the oxygen in the bottom water. It’s a summertime phenomenon, which is why we’re here now—when the Lake is stratified. You get warm surface water over cold bottom water. That cold bottom water is out of contact with the atmosphere. So whatever oxygen is there has to last until the Lake remixes in the fall.”

A Fighting Chance

In addition to adjusting our land-use practices to improve the health of the Great Lakes—no small task in itself—Val also argues we can and should take a moonshot mentality to Great Lakes restoration as a whole. A legacy of industrial abuse and neglect from before the Clean Water Act in the 1970s endowed the Great Lakes with a century of chemical waste that still poisons fish, prevents recreation, hinders development, and requires costly cleanup.

“My feeling is [The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative] should go from an initiative to a program.”

— Val Klump

“I’m a proponent of setting a deadline—a target. We should restore the Great Lakes by 2040 or 2050… It’s our generation’s responsibility to do this. We should not put the responsibility and the costs of doing that on to future generations... Somebody’s got to pay. We should do it now. We can do it now. The Great Lakes regional economy is a $6 trillion economy. It’s the third largest economy in the world. Don’t tell me we can’t afford to do it. We can afford to do it. We just need the will to do it. I’m very encouraged. I see more and more people saying yep, this is something we should take care of. The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative is sort of the initial down-payment on that. But my feeling is it should go from an initiative to a program. We shouldn’t have to fight for this money every year. We should say, okay we’re doing to do this program for the next twenty, thirty years, whatever it takes. So that someday we can say, okay, we’ve restored the system. You’re not going to turn back the clock. The Great Lakes are never going to look like they did a hundred years ago. Those days are all gone. The system has changed. Everything has changed. But we can make them so they’re fishable, swimmable, drinkable. That’s the standard, and that’s what we’re working on.”

As dean of the School of Freshwater Sciences, Val sees its most important mission as educating the next generation so that a wave of talent emerging from a “Freshwater Collaborative” of Wisconsin universities is prepared and inspired to carry the torch of Great Lakes restoration. Not only as academic scientists, but also policymakers, consultants, technicians, nonprofit environmental advocates—a wave of jobs across sectors all united by value for and expertise with water. He notes that globally if you consider water as a business sector, it faces a shortage of talent but a wealth of opportunity.

“I don’t care if you’re a history major, a policy person, or a mud scientist like me! There’s something in this field—there’s a career for you. And it’s an important career because these are big challenges, and very rewarding. These problems are not going to go away. And there are jobs. The water sector is the fastest growing sector of the world economy. All projections I’ve seen say there’s a shortage of people going into this field. So not only is it an important and rewarding career but there are jobs. And 97% of our graduates are working in the field—in water—and they’re working across all different sectors: from academic settings to environmental protection agencies, state and federal, to industry to consulting firms. There’s a real opportunity here.”

“We Need a Bigger Boat”

The Neeskay has operated as a research vessel since 1970.

The Neeskay—a former Army boat built in 1953, retrofitted for research in 1970, and named in the Ho-Chunk language for “pure, clean water”—is the flagship of the School of Freshwater Sciences. Because of the Neeskay, Milwaukee-based and other researchers have been able to perform decades of fundamentally important work to understand and protect the Great Lakes. Having your own research vessel at a university is unique. But the trusty vessel is limited in size and capability. That’s why Val and others have envisioned a next-generation boat. The new research vessel that will replace the Neeskay will be bigger so it can hold more students to support longer cruises to multiple Great Lakes, more lab space to allow for near real-time analysis of samples collected from the water, as well as host a suite of other 21st-century improvements. Thanks to an anonymous donor of $10 million, Val is confident this vision will soon become reality. The new state-of-the-art boat will be built in Wisconsin. The vessel’s name will be the Maggi Sue.

“This would be the first multidisciplinary research vessel built from the keel up for Great Lakes research,” Val says. “It’s been a dream a longtime in the making. What that gift did—it made it a reality. Now—it will happen.”

The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences is raising funds to build the new Maggi Sue research vessel.

Special thanks to Liz Sutton for traveling with the crew of the R/V Neeskay on their late summer 2020 cruise to Green Bay and for conducting the video interview. Editing by Michael Timm with 2020 B-roll footage by Liz Sutton and additional 2013 B-roll footage from Michael Timm and Catherine Simons. Additional thanks to Erik Johnson for sound editing and Katie Schulz for notes on sampling techniques.

Students retrieve a Niskin bottle from the Neeskay in late summer 2020. The bottle captures a water sample from Green Bay and allows for a particular slice of the water column to be analyzed for oxygen saturation and other factors.

The Neeskay has operated as a research vessel since 1970.